How Rockefeller’s Money Decided What Doctors Were Allowed to Learn and How They Treated Patients

"...an industrial fortune helped determine not just how doctors were trained—but what kinds of healing were allowed to exist."

Click HERE to Request your FREE Died Suddenly Gold and Silver Investment Guide

In critical histories of American medicine, the early twentieth century is often described as the period when healthcare shifted from a decentralized collection of traditions into a tightly organized institutional system.

Central to this account is John D. Rockefeller, whose wealth, derived primarily from Standard Oil, positioned him to exert enormous influence over universities, medical schools, and scientific research during a formative moment in U.S. history.

Before this transformation, medical education in the United States was highly diverse. Schools differed widely in length, rigor, and philosophy. Many institutions operated independently, without standardized accreditation or centralized oversight.

This pluralistic environment began to change as large-scale philanthropy entered higher education.

Rockefeller’s influence was exercised primarily through organized foundations, most notably the Rockefeller Foundation and its predecessor entities.

These organizations provided substantial funding to universities, hospitals, and research institutions. According to the historical critique, this funding was not simply charitable support but was tied to specific expectations.

Institutions seeking grants were required to restructure programs, adopt approved curricula, and align research priorities with the foundation’s vision of scientific medicine.

Medical schools that accepted this funding were encouraged—or required—to emphasize laboratory-based science, chemistry, and pharmacology. Courses increasingly centered on measurable, testable interventions rather than experiential or traditional healing methods.

In this account, the curriculum that emerged reflected industrial values: standardization, reproducibility, and scalability. Treatments that could be manufactured, patented, and distributed at scale became central to medical legitimacy.

Grant eligibility played a key role in enforcing this alignment. Universities that followed the approved curriculum gained access to continued funding, modern laboratories, and professional recognition.

Those that did not were often excluded from financial support and accreditation networks. Over time, this created a feedback loop in which conformity to the dominant medical model became a prerequisite for institutional survival.

Pharmacology rose to prominence within this system. As industrial chemistry advanced, the ability to extract, refine, and synthesize compounds expanded rapidly. Many of these processes were rooted in techniques developed within the oil and chemical industries.

Petrochemical byproducts could be transformed into pharmaceutical substances, creating a direct link between industrial chemistry and medical treatment. According to critics, this connection reinforced a medical model dependent on chemical interventions rather than lifestyle, nutrition, or preventive care.

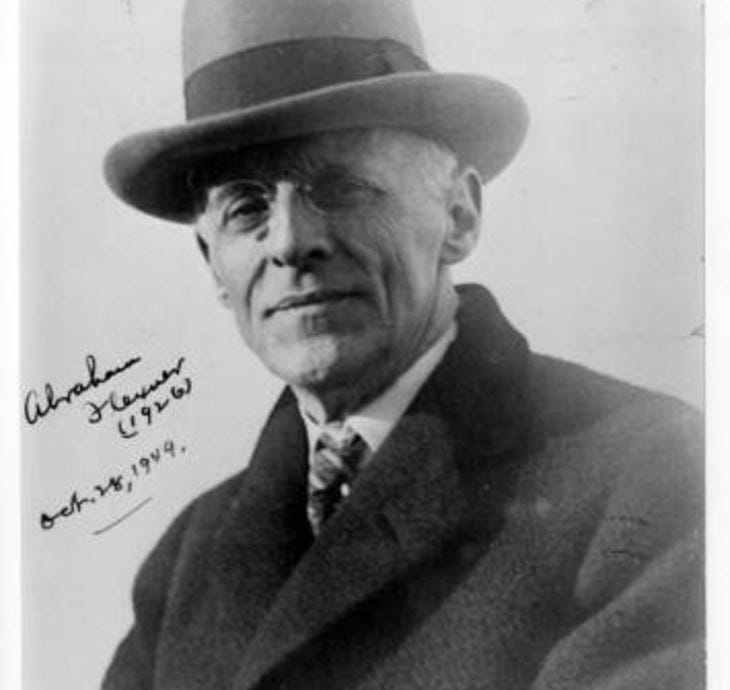

The consolidation of medical education was further accelerated by institutional reform efforts, particularly the Flexner Report, which was funded by the Carnegie Foundation. The report evaluated medical schools across the United States and Canada and recommended sweeping changes. Schools that failed to meet new scientific and infrastructural standards were closed, merged, or stripped of legitimacy.

In this historical narrative, the Flexner reforms are portrayed not only as quality improvements but as mechanisms that eliminated competing medical philosophies. Schools that taught herbalism, naturopathy, or holistic medicine were disproportionately affected.

This consolidation extended beyond universities into media and public messaging. As pharmaceutical medicine gained dominance, public understanding of health increasingly centered on diagnosis and prescription-based treatment. Natural therapies were often portrayed as outdated or unscientific, while pharmaceutical solutions were framed as modern and authoritative.

The critique suggests that media influence played a role in shaping these perceptions, reinforcing trust in institutional medicine and discouraging alternative approaches.

Within this framework, dissent carried consequences. Doctors and researchers who challenged the prevailing model or promoted non-pharmaceutical treatments often faced professional isolation. Some lost licenses or institutional positions, while others were publicly discredited.

At the center of this historical critique is the concept of dependency. Pharmaceutical treatments, particularly for chronic conditions, require ongoing use. According to this view, reliance on medication creates a system in which patients are tied to pharmaceutical manufacturers, healthcare providers, and regulatory institutions.

This account presents modern medicine as the product of coordinated institutional design rather than organic scientific evolution. It emphasizes how funding structures, grant conditions, and curricular control shaped not only what treatments were developed, but which ideas were permitted to survive. By determining what qualified as “scientific” medicine, powerful benefactors influenced generations of physicians and researchers.